Feature

Adding to the Toolbox: Alternatives to Opioids for Managing Pain

by Cara Alexander

Healthcare providers are finding themselves at an alarming intersection of two substantial public health challenges: reducing the epidemic of untreated pain and containing the increasing rates of substance use disorder and opioid-related deaths in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), opioid prescriptions have been declining since 2012,1 signifying that prescribers are becoming increasingly cautious in their prescribing. Although some reduction in prescribing may be attributed to improved practice aimed at maximizing individual and public safety, evidence suggests that pain policy is having a chilling effect on appropriate prescribing.

As policymakers have worked to address opioid misuse through legislative and regulatory efforts, some well-intended policies, such as those that limit prescriptions and scrutinize physician practice, have had the unintended consequence of impeding access to opioids for patients who could benefit and take them safely. A 2018 study conducted by the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN) and the Patient Quality of Life Coalition (PQLC) showed that nearly one-half of cancer patients (48%) and more than one-half of those with other serious illnesses (56%) surveyed said their doctor indicated that treatment options for their pain were limited by laws, guidelines, or insurance coverage.2 At the same time, some clinicians, fearing professional discipline, prosecution, or other penalties, have chosen to cut back on or stop prescribing opioids entirely, even when opioids might be appropriate for their patients.

Bob Twillman, PhD, former executive director of the Academy of Integrative Pain Management and clinical associate professor at the University of Kansas School of Medicine, believes that the current climate leaves many clinicians struggling to determine the best course of treatment. “We are not yet at a point where we are really able to guarantee patients that, if their opioids are reduced or stopped, they will be able to access other types of care that may provide the same degree of pain relief. The simple solution of ‘just say no to opioid prescribing’ generally does not serve patients well and creates substantial risk of the worst possible outcomes,” he said.

Providers are faced with an important question: How can a multidisciplinary team adequately manage pain associated with serious illness in an increasingly restricted environment?

Looking to Alternatives

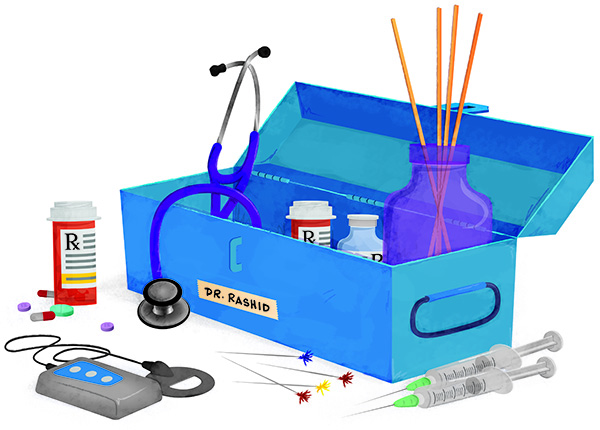

Many hospice and palliative prescribers are finding an answer in nonopioid medications, interventional procedures, and integrative therapies. In addition to supplementing a clinician’s armamentarium, these treatment modalities can provide more comprehensive pain management.

According to Judith Paice, PhD RN, director of the Cancer Pain Program and research professor of medicine for Chicago’s Northwestern University, hospice and palliative care providers have many reasons to look to integrative therapies for pain management. “First, pain can arise from, or be affected by, numerous mechanisms, and by using multiple methods there is greater potential for relief. Second, by using a variety of therapies, the regimen may incorporate lower doses of analgesic agents, possibly resulting in fewer adverse effects,” she said.

Paice pointed out that a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach might incorporate medications from several categories, interventional strategies, and integrative therapies, such as physical, occupational, or cognitive behavioral therapies. These integrative therapies often are overlooked but can have a dramatic impact on a patient’s quality of life.

Nonopioid medication serves as an excellent resource for patients who are not responding appropriately to opioids, according to Mary Lynn McPherson, PharmD MA BCPS CPE, executive director of advanced post-graduate education in palliative care at the University of Maryland. McPherson explained that patients in pain might not respond to opioid therapy for a number of reasons, including disease progression, opioid analgesic tolerance, or opioid-non-responsive pain.

“While the majority of patients with a life-limiting illness will likely require opioid therapy, it is important for practitioners to remember that not all types of pain are 100% opioid responsive,” she said. “Some sources of discomfort may be partially opioid responsive, or not at all. Rational polypharmacy is generally appropriate and certainly welcomed in [cases of] pain of mixed pathology.”

In addition to considering pain that is not responsive to opioids, prescribers must be conscious of the effects of long-term opioid therapy, particularly considering the growing population of patients who are living longer with or surviving serious illness.

Mihir Kamdar, MD, associate director for palliative care and director of the Cancer Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, encourages clinicians to look at interventional procedures as an alternative to long-term opioid therapy. “Particularly in oncology, we are fortunately seeing more and more patients living longer in large part [due] to new and targeted therapies. The question we must ask ourselves is, ‘How do we best manage these patients’ symptoms long term?’” Kamdar said. “Optimizing nonopioid options is critically important. The data suggest that minimally invasive pain interventions can reduce pain and simultaneously improve quality of life by reducing opioid burden and opioid-related side effects.”

Barriers to Integrative Care

Despite the potential benefits of complementary and integrative approaches, incorporating multidisciplinary pain treatment can be a daunting task for hospice and palliative providers—one that involves navigating poor reimbursement, overcoming stigma, and solving policy barriers. One key barrier is that the evidence supporting these treatments does not always meet the threshold required for payers to cover them.

“There actually is a fairly large body of evidence for many nonpharmacological treatments,” Twillman said. “The unfortunate thing is very little of it is [from] randomized controlled trials and very little of it has long-term follow-up. The hang-up is that it’s not the highest quality of evidence.”

A recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine workshop that focused on nonpharmacological approaches to pain management confirmed that reimbursement reform is needed to address the discord between evidence-based practices and payment structures. As it stands, reimbursement policies discourage optimal pain care by providing inadequate coverage for multidisciplinary treatments. This creates an inequity issue because many treatments require patients to pay out of pocket and are not affordable for large portions of the population. The payment structures also undermine multidisciplinary pain treatment by not providing adequate time for clinicians to do a complete assessment.3

A comprehensive assessment is essential for any clinician looking to provide multidisciplinary treatment, said Constance Dahlin, MSN ANP-BC ACHPN FPCN FAAN, director of professional practice for the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. “The comprehensive assessment allows the clinician to get a sense of the patient, [their] expectations around pain, their coping style and how they have coped with pain in the past, their social support, and [their] financial bandwidth for various pain strategies.”

To access a balanced approach to pain management, providers also will have to recognize the stigmatization and marginalization of patients being treated for pain as a significant barrier to care.4 Based on input from public meetings and stakeholder comments, in December 2018, the Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force within the US Department of Health and Human Services issued a 91-page draft report detailing gaps and inconsistencies and proposed updates to best practices and recommendations for pain management, including for chronic and acute pain. Identifying many barriers to treatment, including stigma, the report emphasized that “reducing barriers to care that exist as a consequence of stigmatization is crucial for patient engagement and treatment effectiveness.”5

The American Medical Association (AMA) touched on several of these barriers in its “Opioid Task Force 2018 Progress Report,” to which AAHPM contributed. The report found that although opioid prescribing had decreased nationwide, further policy changes were needed to eliminate the barriers to integrative treatment for pain. “This report underscores that while progress is being made in some areas, our patients need help to overcome barriers to multimodal, multidisciplinary pain care, including nonopioid pain care, as well as relief from harmful policies such as prior authorization and step therapy that delay and deny evidence-based care for opioid use disorder,” Patrice A. Harris, MD MA, chair of the AMA Opioid Take Force, said in a statement.

Finding Solutions

To find solutions that both acknowledge the national crisis of substance use disorder and work to appropriately treat patients’ pain, policymakers must shift away from opioid-driven regulation and begin to craft policies that address pain itself. An example of such an effort was the Integrative Pain Care Policy Congress hosted by the Academy of Integrative Pain Management in 2017 and 2018.

The congress brought together different constituencies in the healthcare space, including clinicians, patients, insurers, researchers, and policymakers, to coalesce around joint strategies for advancing individualized care for people with pain. More than 70 stakeholders came together at the 2017 congress to support the first-ever consensus definition of comprehensive integrative pain management: “comprehensive, integrative pain management includes biomedical, psychosocial, complementary health, and spiritual care. It is person centered and focuses on maximizing function and wellness. Care plans are developed through a shared decision-making model that reflects the available evidence regarding optimal clinical practice and the person’s goals and values.”

Twillman, who helped convene the congress, noted that the consensus definition was a critical step toward defining the shared direction of the field and a tool that could help guide the United States toward an integrative pain treatment focus. In addition to achieving consensus on a definition for comprehensive integrative pain care, participants created an action plan that focused on strategic communications and advocacy, addressing coverage and constraints, promoting comprehensive integrative pain care, data collection and outcomes, and education strategies.

States also have served as catalysts for change by placing considerable emphasis on expanding access to comprehensive, integrative pain treatment. For instance, Ohio, Oregon, and Vermont all have implemented legislation that allows Medicaid recipients to access nonopioid medication and integrative treatment therapies such as acupuncture. A number of states, including Arizona, California, Alaska, Colorado, Arkansas, Alabama, Connecticut, and Delaware, also have developed guidelines that list alternatives to opioids as an important component of treatment plans for chronic pain.6

Statewide pilot programs are exploring alternatives with a limited evidence base as viable treatment options, most recently with the passage of the Opioid Alternative Pilot Program in Illinois. The program, which launched on January 31, allows patients to access medical marijuana as an alternative to opioid prescriptions.

AAHPM Calls for Balanced Policy

AAHPM advocates for balanced pain care and prescribing policy, often by working with stakeholder partners. Through work on the Pain and Palliative Medicine Specialty Section Council in the AMA House of Delegates, AAHPM has been able to help guide policy related to pain care and prescribing, most recently by crafting new policy addressing misapplication of the “CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain.”

In addition, through work on the AMA Opioid Task Force, the AMA Pain Care Task Force, and the Opioid Prescribing Guidelines and Evidence Standards Working Group (which was established under the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Countering the US Opioid Epidemic), AAHPM has been afforded tremendous opportunities to promote pain policy that recognizes patients with legitimate needs and encourages expanded access to many forms of pain management.

Going forward, AAHPM will continue to engage its members and stakeholder partners in efforts to improve the lives of people with pain by advancing a person-centered, integrative model of pain care through greater advocacy.

Refrences

- Guy GP Jr, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(26):697–704.

- New data: some measures meant to address opioid abuse are having adverse impact on access to legitimate pain care for patients [news release]. Washington, DC: American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network; July 14, 2018. https://www.fightcancer.org/releases/new-data-some-measures-meant-address-opioid-abuse-are-having-adverse-impact-access. Accessed April 22, 2018.

- The Role of Nonpharmacological Approaches to Pain Management: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; 2019.

- Carr DB. Patients with pain need less stigma, not more. Pain Med. 2016 Aug;17(8):1391–1393.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. Draft Report on Pain Management Best Practices: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2019. www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/2018-12-draft-report-on-updates-gaps-inconsistencies-recommendations/index.html.

- State Review on Opioid Related Policy. Arizona Dept of Health Services; 2017. https://www.azdhs.gov/documents/prevention/womens-childrens-health/injury-prevention/opioid-prevention/50-state-review-printer-friendly.pdf

Cara Alexander is AAHPM’s manager of health policy and advocacy. She can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .

Read the next article or go to the table of contents.